15 Nov

•

2025

How Iceland Harnessed Geothermal Energy

Read Time

4 min

15 Nov

•

2025

How Iceland Harnessed Geothermal Energy

Read Time

4 min

15 Nov

•

2025

How Iceland Harnessed Geothermal Energy

Read Time

4 min

A model for energy transformation built on geothermal heat and human ingenuity

A model for energy transformation built on geothermal heat and human ingenuity

A model for energy transformation built on geothermal heat and human ingenuity

While it may be hard to believe from the perspective tourists see of Iceland today, before World War II, Iceland was one of the poorest and least developed countries in Europe. The nation was dependent on imported coal and oil to heat homes, for transportation, and to light the long, dark winters. Today, it ranks among the world's wealthiest and most energy-independent nations.

This transformation did not happen overnight. It was shaped by global economic disruptions that forced Iceland to make a bold and lasting decision: to power its future using local resources.

While it may be hard to believe from the perspective tourists see of Iceland today, before World War II, Iceland was one of the poorest and least developed countries in Europe. The nation was dependent on imported coal and oil to heat homes, for transportation, and to light the long, dark winters. Today, it ranks among the world's wealthiest and most energy-independent nations.

This transformation did not happen overnight. It was shaped by global economic disruptions that forced Iceland to make a bold and lasting decision: to power its future using local resources.

While it may be hard to believe from the perspective tourists see of Iceland today, before World War II, Iceland was one of the poorest and least developed countries in Europe. The nation was dependent on imported coal and oil to heat homes, for transportation, and to light the long, dark winters. Today, it ranks among the world's wealthiest and most energy-independent nations.

This transformation did not happen overnight. It was shaped by global economic disruptions that forced Iceland to make a bold and lasting decision: to power its future using local resources.

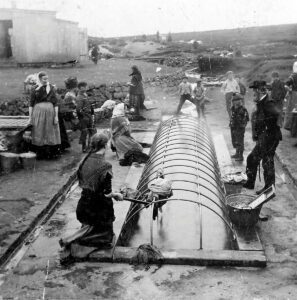

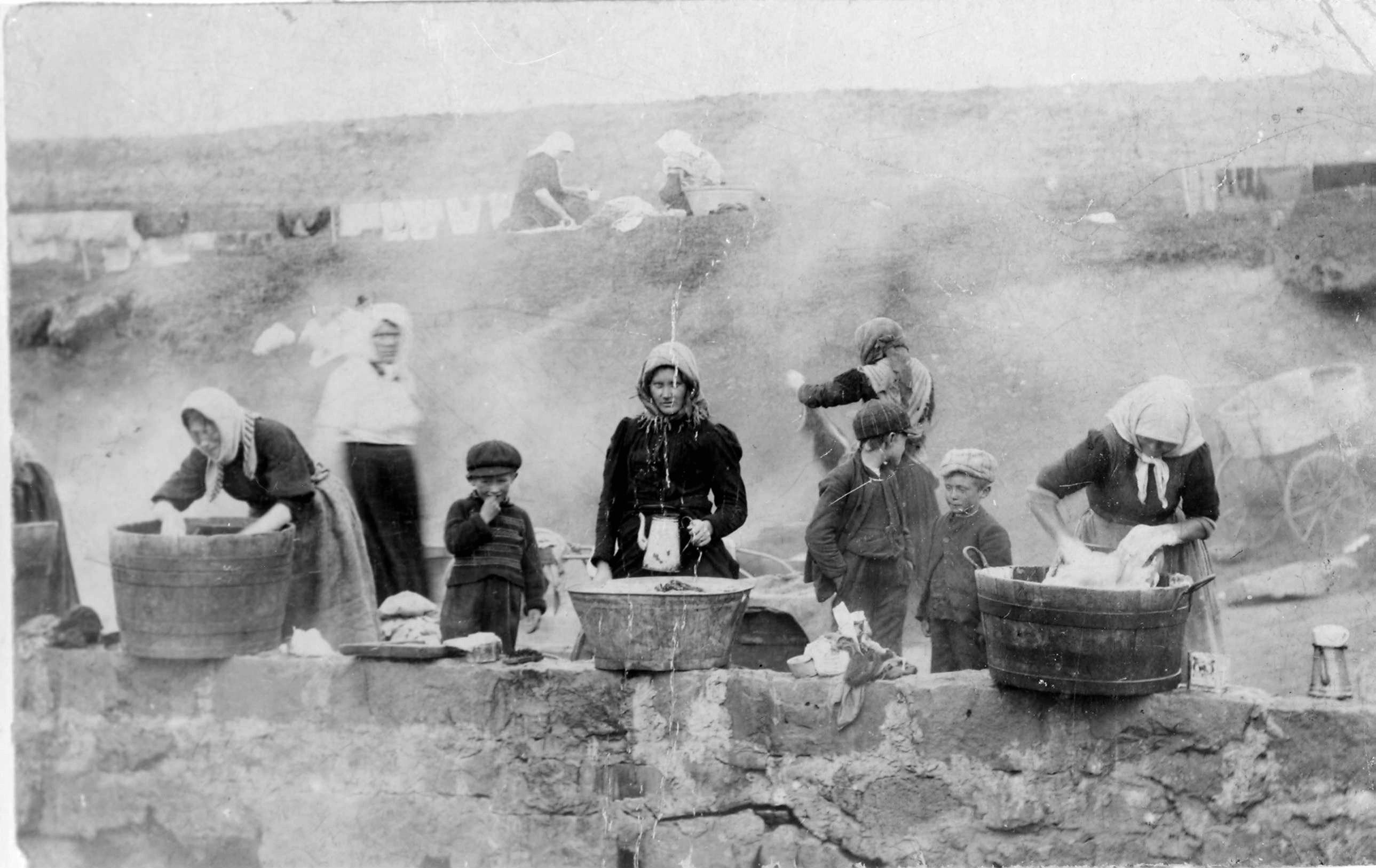

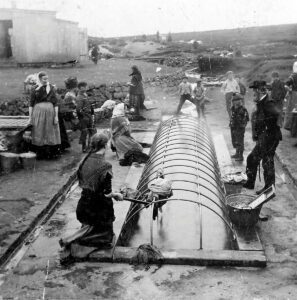

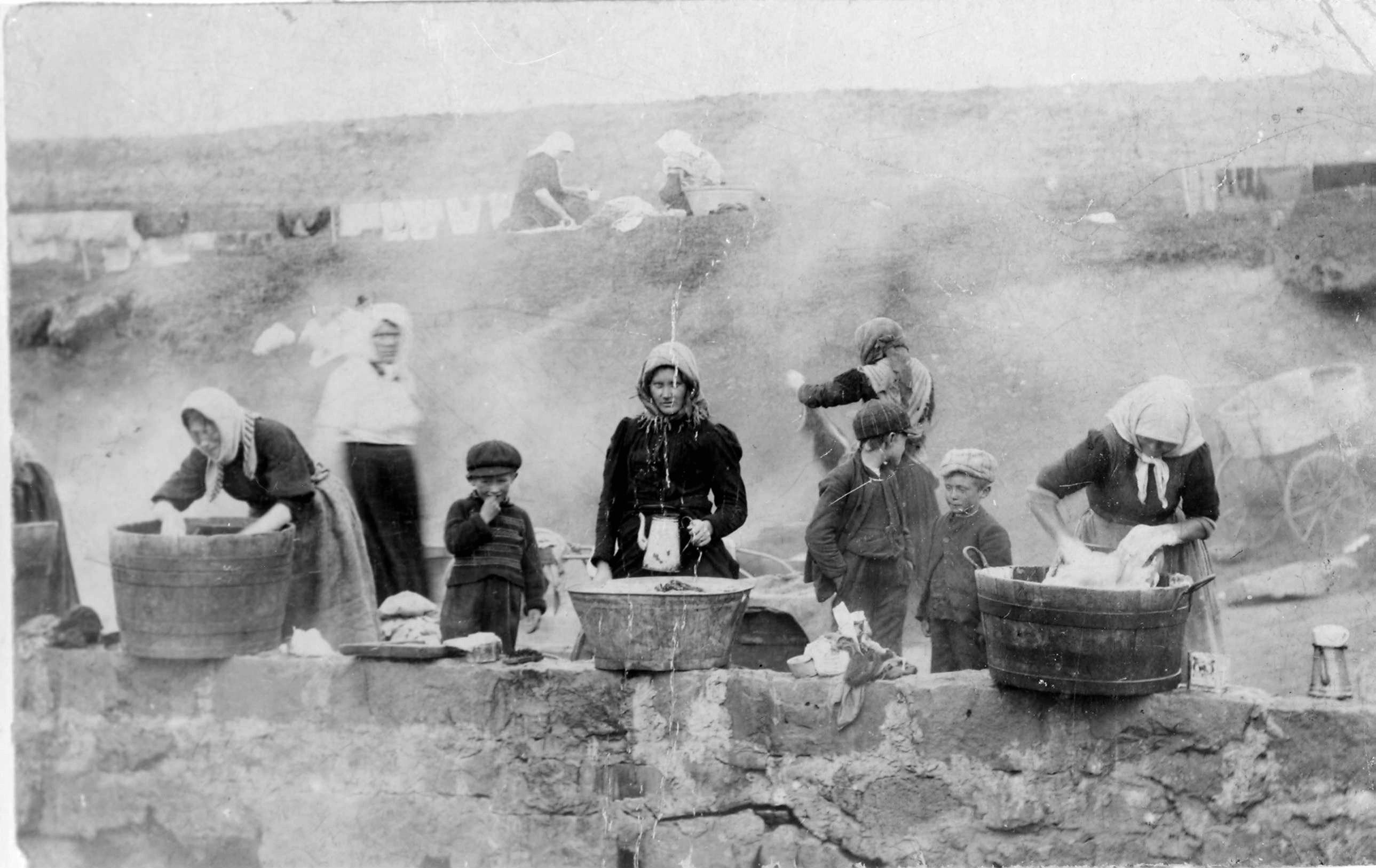

These three photos—spanning more than a century—capture the evolution of Laugardalur in Reykjavík, where Icelanders have long tapped into geothermal energy. From communal laundry washing in hot springs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to today’s popular Laugardalslaug swimming complex, this area tells the story of how Icelanders have continuously harnessed natural hot water for everyday life, community, and recreation.

These three photos—spanning more than a century—capture the evolution of Laugardalur in Reykjavík, where Icelanders have long tapped into geothermal energy. From communal laundry washing in hot springs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to today’s popular Laugardalslaug swimming complex, this area tells the story of how Icelanders have continuously harnessed natural hot water for everyday life, community, and recreation.

These three photos—spanning more than a century—capture the evolution of Laugardalur in Reykjavík, where Icelanders have long tapped into geothermal energy. From communal laundry washing in hot springs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to today’s popular Laugardalslaug swimming complex, this area tells the story of how Icelanders have continuously harnessed natural hot water for everyday life, community, and recreation.

From Fossil Fuel Dependence to Renewable Abundance

From Fossil Fuel Dependence to Renewable Abundance

From Fossil Fuel Dependence to Renewable Abundance

For most of the 20th century, Iceland relied heavily on fossil fuels for heating, electricity, and industrial purposes. However, when the oil crisis struck in 1973, soaring prices and geopolitical instability exposed the risks of energy dependence. The crisis spurred a national shift toward exploring domestic renewable energy options, specifically geothermal and hydropower, laying the foundation for one of the world's most successful energy transitions.

Today, Iceland’s renewable energy mix includes:

Geothermal energy - roughly 30% of electricity

Hydropower - around 70% of electricity

Geothermal heating - provides district heating for about 90% of Icelandic homes

This shift has ensured energy security, stabilized costs, and dramatically reduced emissions.

For most of the 20th century, Iceland relied heavily on fossil fuels for heating, electricity, and industrial purposes. However, when the oil crisis struck in 1973, soaring prices and geopolitical instability exposed the risks of energy dependence. The crisis spurred a national shift toward exploring domestic renewable energy options, specifically geothermal and hydropower, laying the foundation for one of the world's most successful energy transitions.

Today, Iceland’s renewable energy mix includes:

Geothermal energy - roughly 30% of electricity

Hydropower - around 70% of electricity

Geothermal heating - provides district heating for about 90% of Icelandic homes

This shift has ensured energy security, stabilized costs, and dramatically reduced emissions.

For most of the 20th century, Iceland relied heavily on fossil fuels for heating, electricity, and industrial purposes. However, when the oil crisis struck in 1973, soaring prices and geopolitical instability exposed the risks of energy dependence. The crisis spurred a national shift toward exploring domestic renewable energy options, specifically geothermal and hydropower, laying the foundation for one of the world's most successful energy transitions.

Today, Iceland’s renewable energy mix includes:

Geothermal energy - roughly 30% of electricity

Hydropower - around 70% of electricity

Geothermal heating - provides district heating for about 90% of Icelandic homes

This shift has ensured energy security, stabilized costs, and dramatically reduced emissions.

The Rise of Geothermal Heating in Iceland

The Rise of Geothermal Heating in Iceland

The Rise of Geothermal Heating in Iceland

Icelanders have used geothermal hot springs for centuries, but modern utilization began in 1908 when hot water was first piped indoors. In 1928, Reykjavík drilled its first deep well and connected homes to a growing distribution network.

Still, inexpensive imported oil made the expansion of geothermal systems and large-scale infrastructure projects seem expensive by comparison. By the 1970s, the city had set a goal to expand geothermal heating to all homes in the capital area, and other communities with access to geothermal sources followed suit.

When the oil crisis struck, households that were already using geothermal energy were protected from rising energy costs. Meanwhile, the government was forced to subsidize imported oil for the rest of the population. This marked a turning point: Iceland doubled down on its geothermal resources and began the transition to entirely domestic energy for heating.

Ironically, to accelerate the exploration process, the government and local energy companies repurposed oil drilling rigs and equipment, adapting them to explore geothermal reservoirs nationwide.

The benefits went far beyond cost savings. Geothermal now supports:

Electricity generation (750+ MW installed)

Greenhouse agriculture and local food production

Spas and wellness tourism

Carbon capture and synthetic fuels

Biotech, cosmetics, and heated public infrastructure

Education, training, engineering, and international knowledge sharing

The dividends? Cleaner environment, energy security, affordable heat and electricity that support economic growth, and enhance the health and quality of life of citizens throughout the year.

Icelanders have used geothermal hot springs for centuries, but modern utilization began in 1908 when hot water was first piped indoors. In 1928, Reykjavík drilled its first deep well and connected homes to a growing distribution network.

Still, inexpensive imported oil made the expansion of geothermal systems and large-scale infrastructure projects seem expensive by comparison. By the 1970s, the city had set a goal to expand geothermal heating to all homes in the capital area, and other communities with access to geothermal sources followed suit.

When the oil crisis struck, households that were already using geothermal energy were protected from rising energy costs. Meanwhile, the government was forced to subsidize imported oil for the rest of the population. This marked a turning point: Iceland doubled down on its geothermal resources and began the transition to entirely domestic energy for heating.

Ironically, to accelerate the exploration process, the government and local energy companies repurposed oil drilling rigs and equipment, adapting them to explore geothermal reservoirs nationwide.

The benefits went far beyond cost savings. Geothermal now supports:

Electricity generation (750+ MW installed)

Greenhouse agriculture and local food production

Spas and wellness tourism

Carbon capture and synthetic fuels

Biotech, cosmetics, and heated public infrastructure

Education, training, engineering, and international knowledge sharing

The dividends? Cleaner environment, energy security, affordable heat and electricity that support economic growth, and enhance the health and quality of life of citizens throughout the year.

“We have the vote,” said writer and parliamentarian Svava Jakobsdóttir, speaking at Reykjavík’s Women’s Day Off rally on October 24, 1975. “And we’re proud of it. But what we seem to forget is that we also fought for the right to run for office.”

Her words came six decades after Icelandic women had won the vote. Yet by 1975, only nine women had ever served in parliament. At the time, just three women, a mere 5% of Alþingi members, held seats, and that was the highest number to date. Only one woman had ever served as a cabinet minister, and for just one year, in 1970.

In comparison, the other Nordic countries had already moved ahead, with women making up 14–26% of their national parliaments and frequently serving in government. Local representation in Iceland was even lower: women made up less than 4% of municipal representatives in 1975.

Geothermal hot water has made Iceland a global destination for spa and wellness tourism, with facilities like the Forest Lagoon in North Iceland offering year-round relaxation in naturally heated pools surrounded by nature.

The parliamentarians Svava Jakobsdóttir and Sigurlaug Bjarnadóttir deliver a speech to motivate the members of parliament on Women’s Day in 1975. Photographer unknown. Preservation: Women’s History Archive of Iceland.

Geothermal hot water has made Iceland a global destination for spa and wellness tourism, with facilities like the Forest Lagoon in North Iceland offering year-round relaxation in naturally heated pools surrounded by nature.

Policy, Innovation, and Industry

Policy, Innovation, and Industry

Policy, Innovation, and Industry

Iceland's shift wasn't just technical; it was strategic. The government utilized tools such as the Energy Fund to finance geothermal exploration and grid development, working closely with local utilities and researchers. Public-private collaboration ensured that infrastructure expanded equitably, while also attracting power-intensive industries, such as aluminum smelters and, later, data centers, circular industrial parks, and land-based aquaculture, which now operate with some of the lowest carbon footprints in the world.

Iceland's shift wasn't just technical; it was strategic. The government has played a central role through initiatives such as:

The Energy Fund, which financed geothermal exploration

Public-private collaboration between municipalities, utilities, and researchers

Infrastructure investments enabling large-scale district heating

Partnerships that attracted energy-intensive industries with low-carbon power, such as aluminum smelters, data centers, and land-based aquaculture

Today, Iceland continues to innovate, with cutting-edge projects such as Carbfix and Climeworks, which focus on carbon removal and sequestration, as well as innovative companies like Carbon Recycling International that explore the next frontier in clean energy through green fuels.

Iceland's shift wasn't just technical; it was strategic. The government utilized tools such as the Energy Fund to finance geothermal exploration and grid development, working closely with local utilities and researchers. Public-private collaboration ensured that infrastructure expanded equitably, while also attracting power-intensive industries, such as aluminum smelters and, later, data centers, circular industrial parks, and land-based aquaculture, which now operate with some of the lowest carbon footprints in the world.

Iceland's shift wasn't just technical; it was strategic. The government has played a central role through initiatives such as:

The Energy Fund, which financed geothermal exploration

Public-private collaboration between municipalities, utilities, and researchers

Infrastructure investments enabling large-scale district heating

Partnerships that attracted energy-intensive industries with low-carbon power, such as aluminum smelters, data centers, and land-based aquaculture

Today, Iceland continues to innovate, with cutting-edge projects such as Carbfix and Climeworks, which focus on carbon removal and sequestration, as well as innovative companies like Carbon Recycling International that explore the next frontier in clean energy through green fuels.

Iceland's shift wasn't just technical; it was strategic. The government utilized tools such as the Energy Fund to finance geothermal exploration and grid development, working closely with local utilities and researchers. Public-private collaboration ensured that infrastructure expanded equitably, while also attracting power-intensive industries, such as aluminum smelters and, later, data centers, circular industrial parks, and land-based aquaculture, which now operate with some of the lowest carbon footprints in the world.

Iceland's shift wasn't just technical; it was strategic. The government has played a central role through initiatives such as:

The Energy Fund, which financed geothermal exploration

Public-private collaboration between municipalities, utilities, and researchers

Infrastructure investments enabling large-scale district heating

Partnerships that attracted energy-intensive industries with low-carbon power, such as aluminum smelters, data centers, and land-based aquaculture

Today, Iceland continues to innovate, with cutting-edge projects such as Carbfix and Climeworks, which focus on carbon removal and sequestration, as well as innovative companies like Carbon Recycling International that explore the next frontier in clean energy through green fuels.

Keep your eyes open. Geothermal boreholes like this one are a common sight around Reykjavík, quietly tapping into the earth’s natural heat to supply clean, renewable hot water and heating to homes, businesses, and public buildings across the city.

A statue of Ingibjörg H. Bjarnason unveiled in front of Alþingi in 2015, marking the 100th anniversary of women's suffrage in Iceland.

Keep your eyes open. Geothermal boreholes like this one are a common sight around Reykjavík, quietly tapping into the earth’s natural heat to supply clean, renewable hot water and heating to homes, businesses, and public buildings across the city.

Local Success turns to Global Resource

Local Success turns to Global Resource

Local Success turns to Global Resource

What began as an economic survival tactic has evolved into a global model. Notably, sharing geothermal expertise is one of Iceland's most successful exports. Engineering firms, scientists, and legal advisors now support clean energy projects around the world.

Icelandic geothermal experts have assisted dozens of countries in developing their own geothermal systems, ranging from Kenya to Indonesia. Since 1978, over 700 professionals from developing countries have graduated from Iceland's UN geothermal training program, now under UNESCO, helping to disseminate knowledge and build capacity to harness geothermal energy effectively.

What began as an economic survival tactic has evolved into a global model. Notably, sharing geothermal expertise is one of Iceland's most successful exports. Engineering firms, scientists, and legal advisors now support clean energy projects around the world.

Icelandic geothermal experts have assisted dozens of countries in developing their own geothermal systems, ranging from Kenya to Indonesia. Since 1978, over 700 professionals from developing countries have graduated from Iceland's UN geothermal training program, now under UNESCO, helping to disseminate knowledge and build capacity to harness geothermal energy effectively.

What began as an economic survival tactic has evolved into a global model. Notably, sharing geothermal expertise is one of Iceland's most successful exports. Engineering firms, scientists, and legal advisors now support clean energy projects around the world.

Icelandic geothermal experts have assisted dozens of countries in developing their own geothermal systems, ranging from Kenya to Indonesia. Since 1978, over 700 professionals from developing countries have graduated from Iceland's UN geothermal training program, now under UNESCO, helping to disseminate knowledge and build capacity to harness geothermal energy effectively.

Next Phase of Iceland’s Renewable Energy Expansion

Next Phase of Iceland’s Renewable Energy Expansion

Next Phase of Iceland’s Renewable Energy Expansion

1. Was Iceland’s transition to geothermal energy a choice or a necessity?

It was a strategic response to economic vulnerability. While Iceland was already a developing and relatively prosperous nation by the 1970s, the 1973 oil crisis exposed a major weakness: half of the population still relied on imported oil for heating. When global prices surged, the government made a bold policy shift to eliminate oil in favor of domestic geothermal reservoirs. This wasn't an escape from poverty, but a calculated move toward permanent energy independence.

2. What are "cold areas" and why is the government still funding them?

In Iceland, "cold areas" refers to regions where geothermal potential was historically thought to be too low or too deep to reach affordably. Today, roughly 10% of Icelandic homes in these areas still rely on electricity or oil for heating. Through the 2024 initiative Jarðhiti jafnar leikinn ("Geothermal Levels the Playing Field"), the government is investing 1 billion ISK to explore low-temperature zones in these regions. The goal is to ensure every household has access to stable, low-cost heating regardless of geography.

3. How does geothermal heat actually reach individual homes?

Iceland uses a vast "district heating" network. Naturally hot water is pumped from underground reservoirs into a web of insulated pipes that run beneath cities and towns. This water is delivered directly to houses for space heating and tap water. Because the water travels through highly insulated pipes, it loses very little heat—even over long distances—providing one of the most efficient heating systems in the world.

4. Is this technology an "Iceland-only" solution?

No. While Iceland’s volcanic geology provided a perfect testbed, the principles are global. Many countries have "low-temperature" geothermal zones that can support space heating, even if they aren't hot enough for electricity generation. Iceland now exports this expertise through engineering firms and the UNESCO Geothermal Training Programme, which has trained over 700 professionals from dozens of countries to help them map and harness their own local heat.

5. How does geothermal energy support a "Circular Economy"?

Geothermal energy is rarely used just once. In what is called a "cascaded" model, the energy is used in stages. High-temperature steam first generates electricity. The remaining heat is then used for district heating. Once the water has warmed a house, it still carries enough residual heat to be used for greenhouse farming, land-based aquaculture, or melting snow from city sidewalks and parking lots.

6. Why does the hot water sometimes smell like sulfur (or "rotten eggs")?

That scent is a sign of the water’s direct connection to the earth. In most of Iceland, hot water is pumped directly from geothermal reservoirs. It contains trace amounts of naturally occurring hydrogen sulfide ($H_2S$) from volcanic environments.

While the smell might be surprising at first, it serves a critical purpose beyond being a sign of purity. The hydrogen sulfide naturally reacts with and removes oxygen from the water. Because oxygen is the primary cause of rust in metal, this "de-oxygenated" water prevents the country's massive network of steel pipes from corroding. By utilizing the water's natural chemistry, Iceland maintains a vast infrastructure that lasts for decades without the need for heavy chemical additives. It is perfectly safe for showering and bathing.

Pro tip: Only the hot water has this scent. Iceland’s cold water comes from high-quality glacial and spring sources and is some of the cleanest drinking water in the world. To avoid the scent when drinking, always let the cold tap run for a few seconds until the water is ice-cold.

1. Was Iceland’s transition to geothermal energy a choice or a necessity?

It was a strategic response to economic vulnerability. While Iceland was already a developing and relatively prosperous nation by the 1970s, the 1973 oil crisis exposed a major weakness: half of the population still relied on imported oil for heating. When global prices surged, the government made a bold policy shift to eliminate oil in favor of domestic geothermal reservoirs. This wasn't an escape from poverty, but a calculated move toward permanent energy independence.

2. What are "cold areas" and why is the government still funding them?

In Iceland, "cold areas" refers to regions where geothermal potential was historically thought to be too low or too deep to reach affordably. Today, roughly 10% of Icelandic homes in these areas still rely on electricity or oil for heating. Through the 2024 initiative Jarðhiti jafnar leikinn ("Geothermal Levels the Playing Field"), the government is investing 1 billion ISK to explore low-temperature zones in these regions. The goal is to ensure every household has access to stable, low-cost heating regardless of geography.

3. How does geothermal heat actually reach individual homes?

Iceland uses a vast "district heating" network. Naturally hot water is pumped from underground reservoirs into a web of insulated pipes that run beneath cities and towns. This water is delivered directly to houses for space heating and tap water. Because the water travels through highly insulated pipes, it loses very little heat—even over long distances—providing one of the most efficient heating systems in the world.

4. Is this technology an "Iceland-only" solution?

No. While Iceland’s volcanic geology provided a perfect testbed, the principles are global. Many countries have "low-temperature" geothermal zones that can support space heating, even if they aren't hot enough for electricity generation. Iceland now exports this expertise through engineering firms and the UNESCO Geothermal Training Programme, which has trained over 700 professionals from dozens of countries to help them map and harness their own local heat.

5. How does geothermal energy support a "Circular Economy"?

Geothermal energy is rarely used just once. In what is called a "cascaded" model, the energy is used in stages. High-temperature steam first generates electricity. The remaining heat is then used for district heating. Once the water has warmed a house, it still carries enough residual heat to be used for greenhouse farming, land-based aquaculture, or melting snow from city sidewalks and parking lots.

6. Why does the hot water sometimes smell like sulfur (or "rotten eggs")?

That scent is a sign of the water’s direct connection to the earth. In most of Iceland, hot water is pumped directly from geothermal reservoirs. It contains trace amounts of naturally occurring hydrogen sulfide ($H_2S$) from volcanic environments.

While the smell might be surprising at first, it serves a critical purpose beyond being a sign of purity. The hydrogen sulfide naturally reacts with and removes oxygen from the water. Because oxygen is the primary cause of rust in metal, this "de-oxygenated" water prevents the country's massive network of steel pipes from corroding. By utilizing the water's natural chemistry, Iceland maintains a vast infrastructure that lasts for decades without the need for heavy chemical additives. It is perfectly safe for showering and bathing.

Pro tip: Only the hot water has this scent. Iceland’s cold water comes from high-quality glacial and spring sources and is some of the cleanest drinking water in the world. To avoid the scent when drinking, always let the cold tap run for a few seconds until the water is ice-cold.

1. Was Iceland’s transition to geothermal energy a choice or a necessity?

It was a strategic response to economic vulnerability. While Iceland was already a developing and relatively prosperous nation by the 1970s, the 1973 oil crisis exposed a major weakness: half of the population still relied on imported oil for heating. When global prices surged, the government made a bold policy shift to eliminate oil in favor of domestic geothermal reservoirs. This wasn't an escape from poverty, but a calculated move toward permanent energy independence.

2. What are "cold areas" and why is the government still funding them?

In Iceland, "cold areas" refers to regions where geothermal potential was historically thought to be too low or too deep to reach affordably. Today, roughly 10% of Icelandic homes in these areas still rely on electricity or oil for heating. Through the 2024 initiative Jarðhiti jafnar leikinn ("Geothermal Levels the Playing Field"), the government is investing 1 billion ISK to explore low-temperature zones in these regions. The goal is to ensure every household has access to stable, low-cost heating regardless of geography.

3. How does geothermal heat actually reach individual homes?

Iceland uses a vast "district heating" network. Naturally hot water is pumped from underground reservoirs into a web of insulated pipes that run beneath cities and towns. This water is delivered directly to houses for space heating and tap water. Because the water travels through highly insulated pipes, it loses very little heat—even over long distances—providing one of the most efficient heating systems in the world.

4. Is this technology an "Iceland-only" solution?

No. While Iceland’s volcanic geology provided a perfect testbed, the principles are global. Many countries have "low-temperature" geothermal zones that can support space heating, even if they aren't hot enough for electricity generation. Iceland now exports this expertise through engineering firms and the UNESCO Geothermal Training Programme, which has trained over 700 professionals from dozens of countries to help them map and harness their own local heat.

5. How does geothermal energy support a "Circular Economy"?

Geothermal energy is rarely used just once. In what is called a "cascaded" model, the energy is used in stages. High-temperature steam first generates electricity. The remaining heat is then used for district heating. Once the water has warmed a house, it still carries enough residual heat to be used for greenhouse farming, land-based aquaculture, or melting snow from city sidewalks and parking lots.

6. Why does the hot water sometimes smell like sulfur (or "rotten eggs")?

That scent is a sign of the water’s direct connection to the earth. In most of Iceland, hot water is pumped directly from geothermal reservoirs. It contains trace amounts of naturally occurring hydrogen sulfide ($H_2S$) from volcanic environments.

While the smell might be surprising at first, it serves a critical purpose beyond being a sign of purity. The hydrogen sulfide naturally reacts with and removes oxygen from the water. Because oxygen is the primary cause of rust in metal, this "de-oxygenated" water prevents the country's massive network of steel pipes from corroding. By utilizing the water's natural chemistry, Iceland maintains a vast infrastructure that lasts for decades without the need for heavy chemical additives. It is perfectly safe for showering and bathing.

Pro tip: Only the hot water has this scent. Iceland’s cold water comes from high-quality glacial and spring sources and is some of the cleanest drinking water in the world. To avoid the scent when drinking, always let the cold tap run for a few seconds until the water is ice-cold.

Even as Iceland already harnesses an impressive share of its geothermal resources, the nation remains committed to expanding access and encourages innovation. In 2024, the Icelandic government launched a major initiative called Geothermal Levels the Playing Field (Jarðhiti jafnar leikinn), committing 1 billion ISK (approximately USD 7.4 million) to support municipalities and utilities.

The funding is aimed at exploring low-temperature geothermal zones for direct heating in so-called “cold areas,” those regions previously thought to lack sufficient geothermal potential and still reliant on oil or electricity for home heating.

Roughly 10% of Icelandic homes still rely on these more expensive and carbon-intensive energy sources, and the new funding aims to close that gap.

By targeting projects that build on existing geothermal research and infrastructure, Iceland is not only reducing emissions and subsidies but also reinforcing geothermal as a smart, future-focused investment. It’s a clear signal that the country’s energy transition is still advancing, and that geothermal remains central to Iceland’s clean energy leadership.

Iceland's story is not a one-off. Many countries have untapped geothermal potential, from high-temperature zones for electricity to lower-temperature resources for space heating. Furthermore, geothermal offers a scalable, local solution with a wide variety of applications.

Iceland demonstrates that a fossil-free future is not only possible but also practical. With the right mix of policy, governmental support, innovation, and long-term commitment, others can follow Iceland's path toward a cleaner, more secure energy future.

Even as Iceland already harnesses an impressive share of its geothermal resources, the nation remains committed to expanding access and encourages innovation. In 2024, the Icelandic government launched a major initiative called Geothermal Levels the Playing Field (Jarðhiti jafnar leikinn), committing 1 billion ISK (approximately USD 7.4 million) to support municipalities and utilities.

The funding is aimed at exploring low-temperature geothermal zones for direct heating in so-called “cold areas,” those regions previously thought to lack sufficient geothermal potential and still reliant on oil or electricity for home heating.

Roughly 10% of Icelandic homes still rely on these more expensive and carbon-intensive energy sources, and the new funding aims to close that gap.

By targeting projects that build on existing geothermal research and infrastructure, Iceland is not only reducing emissions and subsidies but also reinforcing geothermal as a smart, future-focused investment. It’s a clear signal that the country’s energy transition is still advancing, and that geothermal remains central to Iceland’s clean energy leadership.

Iceland's story is not a one-off. Many countries have untapped geothermal potential, from high-temperature zones for electricity to lower-temperature resources for space heating. Furthermore, geothermal offers a scalable, local solution with a wide variety of applications.

Iceland demonstrates that a fossil-free future is not only possible but also practical. With the right mix of policy, governmental support, innovation, and long-term commitment, others can follow Iceland's path toward a cleaner, more secure energy future.

Even as Iceland already harnesses an impressive share of its geothermal resources, the nation remains committed to expanding access and encourages innovation. In 2024, the Icelandic government launched a major initiative called Geothermal Levels the Playing Field (Jarðhiti jafnar leikinn), committing 1 billion ISK (approximately USD 7.4 million) to support municipalities and utilities.

The funding is aimed at exploring low-temperature geothermal zones for direct heating in so-called “cold areas,” those regions previously thought to lack sufficient geothermal potential and still reliant on oil or electricity for home heating.

Roughly 10% of Icelandic homes still rely on these more expensive and carbon-intensive energy sources, and the new funding aims to close that gap.

By targeting projects that build on existing geothermal research and infrastructure, Iceland is not only reducing emissions and subsidies but also reinforcing geothermal as a smart, future-focused investment. It’s a clear signal that the country’s energy transition is still advancing, and that geothermal remains central to Iceland’s clean energy leadership.

Iceland's story is not a one-off. Many countries have untapped geothermal potential, from high-temperature zones for electricity to lower-temperature resources for space heating. Furthermore, geothermal offers a scalable, local solution with a wide variety of applications.

Iceland demonstrates that a fossil-free future is not only possible but also practical. With the right mix of policy, governmental support, innovation, and long-term commitment, others can follow Iceland's path toward a cleaner, more secure energy future.